Their Alphabet Started It All

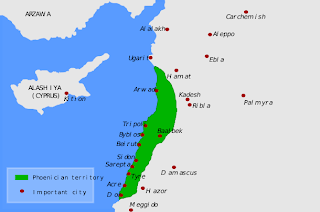

The

Phoenicians were members of an ancient civilization based in the north of

ancient Canaan, which approximates today’s modern Lebanon. Their civilization was a trading maritime culture that spread across the

Mediterranean from 1550 BC to 300 BC, a period in history when there was no

major military power in Mesopotamia, thus enabling smaller states like

Phoenicia and the Hebrews to prosper.

The term “Phoenicia” was actually

from a Greek word that referred to the color of the dye from the snail murex; the Phoenicians, however,

referred to themselves as the “Kena’ani,”

(or “Canaanites”), which incidentally is also a Hebrew word for “merchant.”

Although the Phoenicians

considered themselves a single nation, Phoenicia was not a unified state but a

group of city-kingdoms, much like the ancient Greek city-states. The

most important of these cities were Simyra, Zarephath (Sarafand), Byblos,

Jubeil, Arwad (Rouad), Acco (‘Akko), Sidon (Şaydā), Tripolis (Tripoli), Tyre

(Sur), and Berytus (Beirut). The two most powerful were Tyre and Sidon, which

alternated as sites of the ruling power.

Called Sidonians or Canaanites in the Old Testament, they founded their

first settlements on the Mediterranean coast about 2500 BC. The Phoenicians

developed their culture under the influence of the Sumerians and Akkadians of

Mesopotamia. Around 1800 BC, the Egyptians invaded and conquered Phoenicia.

Raids on Egyptian territory by the Hittites around 1400 BC weakened the

Egyptians, providing the Phoenicians an opportunity to revolt; by 1200 BC they

succeeded in driving out the Egyptians.

Phoenicia comprised an area that is now modern Lebanon and parts of Syria

and Israel. As the territory was small, Phoenicians were forced to turn to the

sea for a living. They were the most skillful shipbuilders and navigators of

their time. They founded colonies all over the Mediterranean, even reaching as

far as Spain and the British Isles. Their most important colony was Carthage in

North Africa.

|

| Hannibal, one of history's greatest generals, was from Carthage |

Monarchy was Phoenicia’s oldest form of government. Kings could not be

chosen outside the royal family, as members of the royal family claimed they

were descended from the gods. The king’s power, however, was not absolute.

Powerful merchants who possessed great influence in public affairs largely

limited the power wielded by the king. The kings in the cities of Byblos,

Sidon, and Tyre had a council of elders to assist them in their duties. Later,

other Phoenician cities adopted a form of republican government in place of the

monarchy. Instead of a king, a suffete,

or a judge, ruled some of these city-states.

With mountains to their east and the Mediterranean to their west,

Phoenicia’s geography proved ideal for trade during this era. The Phoenicians

were able to exploit the small arable land in the mountain slopes, and use the

watercourses for irrigation, a system of cultivation that was in use up to the

20th century. Phoenicia was also famous for its cedar and fir

forests, which provided neighboring countries with valuable wood, and for the

purple dye, the “Tyrean purple.” This dye, obtained from the snail murex, was so expensive that only kings

and members of the nobility could afford garments dyed with it. Ivory,

woodcarvings, linen, wine, metal works, and glass are some of the products that

were traded by these people. The invention of glass is also credited to the

Phoenicians.

A Phoenician king, Hiram, is also mentioned in the Old Testament as an ally of King David and later of King Solomon, whose temple King Hiram helped build.

They are also famous for their maritime exploits. Besides founding colonies

throughout the Mediterranean, there is also evidence of Phoenician mariners having reached the New World, well before Columbus did so in the 15th

century. After developing the technical knowledge for navigating the high seas,

the Phoenicians mastered almost all of the sectors of economy: from

exploitation of the mineral and agricultural resources, to their

transformation, and commercialization through a remarkable chain of

distribution.

Due to their sea-faring capabilities, they were able to reach many

markets, taking the fine wares of Eastern Europe to trade with the Western

barbarians. In addition, they learned to manufacture the wares themselves, and

they adapted to the taste of the buyers in different countries around the

Mediterranean Sea. This meant that they did not only offer luxury goods to rich

customers, but they also had low-priced goods for the masses as well. We can

say therefore that the Phoenician Empire was built not through military

exploits, but through trade.

The

Phoenicians’ maritime tradition would not have been possible without their

nautical technology. Their ships had designs that were pretty advanced for

their time, and their navigational skills where the envy of the ancient world.

In fact, they provided Persia with ships and mariners during Persia’s

unsuccessful attempt to conquer Greece. The Phoenicians were also the first to

use Polaris (the North Star) in navigation.

Probably the greatest contribution of the Phoenicians to humanity was

their alphabet, which was developed around 1000 BC at Byblos (incidentally,

from this city’s name comes the Greek word biblia—books—and the English word “bible”).

This 22-character alphabet greatly simplified writing; before this, people had

to create thousands of symbols for the thousands of words in their language.

The Phoenician alphabet uses the 22 characters to represent 22 different

sounds, which form a word when strung together. This type of alphabet is also

known as “phonetic” alphabet. Guess where the term comes from.

Phoenicians spread this style in their travels and greatly influenced

Greek and other alphabets.

Although Phoenician city-states never constituted a single political

entity, there was a cultural identity among the Phoenicians, mainly because of

a common language. In this society, wealthy merchant aristocrats enjoyed

protection from the law. Below the aristocracy were the lesser merchants,

artisans, and shopkeepers. A rung below the social ladder were the average

workers, and at the bottom were the slaves. Slaves had little protection from

the laws, but they could earn money and could even buy their own freedom.

Women in this society relatively had a bit more freedom than in any other

society of this era. They could initiate divorce proceedings, they could engage

in business, and they could bring issues to legal courts. Not much of a

freedom, though. Women were made to cover up carefully with layers of clothing

when going out in public, and were often relegated to work in menial jobs, like

weaving textiles. They had no say in government affairs.

Phoenicians are known for their pantheistic religion (belief in many

gods). Each city-state had its own special deity (kind of like a “patron”

deity), usually called Baal, or lord. A pantheon (temple) was presided over by

the chief god, “El.” The principal figure in Phoenician pantheons, however, was

Astarte (a.k.a. Ishtar).

|

| In Phoenicia, she is known as Astarte |

The Phoenicians’ culture and language resemble those of the other Semitic

peoples living in the area. Because of their maritime tradition, they were able

to spread this culture to other places in the Mediterranean rim. Their art also

had no unique characteristics that could be identified as purely Phoenician;

they were heavily influenced by foreign artistic and cultural traditions, such

as the Egyptians, Greeks, Assyrians, and Persians. As a result, their art was a

mixture of the different styles of the many civilizations that conquered their

lands.

Phoenicia reached its peak shortly after they achieved self-rule with the

Egyptians’ expulsion from their lands. Their fleets traveled throughout the

Mediterranean and even reached the Atlantic Ocean. Other nations employed

Phoenician ships and mariners in their navies. Phoenicians also founded many

colonies, most notable of which, besides Carthage in North Africa, were Utica

(also in North Africa), Rhodes and Cyprus in the Mediterranean Sea, and

Tarshish in Spain. In the 8th century, Phoenicia, then under the

leadership of Tyre, was conquered by Assyria. After the fall of the Assyrian

Empire, the city-states were added into Nebuchadnezzar II’s Chaldean Empire. In

539 BC, they became part of the Persian Empire.

Alexander the Great then conquered the Persians; several city-states of

Phoenicia quickly surrendered to the Macedonian conqueror, except for Tyre.

Alexander conquered Tyre in 332 BC only after a seven-month siege. Phoenicia

gradually lost its identity after this defeat. The inhabitants were absorbed into

Alexander’s empire, and the cities became Hellenized (became Greek-like). In 64

BC, the territory became a province of the Roman Empire called Syria.

In the year 630, Islamic Arabs conquered the area of what used to be

Phoenicia, almost without any resistance.

Comments

Post a Comment

So, what do you think? Post it here: